What we are living through and talking about – at too much length, please forgive me – occupies the time and place of a miniscule comma in an infinite text.

Jacques Derrida, Paper Machine

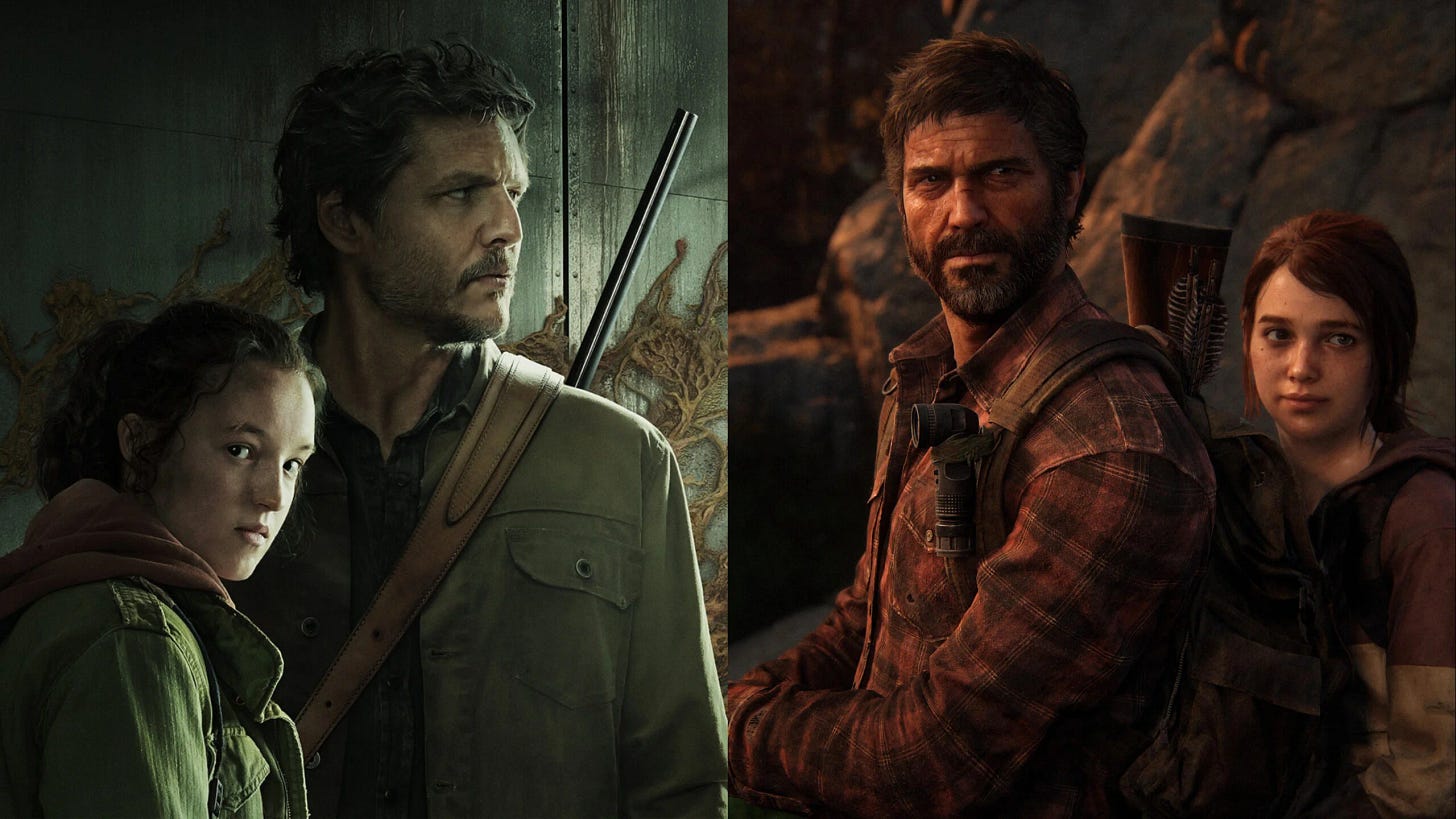

23 years after Total Recall side-scrolled its way onto the NES, The Last of Us was released on PlayStation 3. Ten years later, it reversed Arnold’s journey by becoming a big-budget TV show.

The PhD behind the essays being uploaded here was about what happens to stories when they go through movements like the above: do they change when being told through a game? My answer involved the first thing you notice when comparing examples like these two: games change, and they change really fast.

The characters in The Last of Us look more like real people than those in Total Recall. They have more human voices; they show more emotion; they move around the world in more dimensions. There are more lines of code in the software, more transistors in the hardware. More nuance to the story and more pixels on the screen.

Put the two games side by side and they’re barely recognisable as being from the same medium. Put The Last of Us next to its own sequel, and the effect is less pronounced but still there: games feel like they’re growing, changing, improving; evolving into something ever more complex.

This was ultimately the core argument of my thesis: that playing a game means experiencing this process, this feeling that the medium is always advancing. And advancing towards something…

..two fantasmatic limits of the book to come, two extreme, final, eschatic figures of the end of the book: the end as death, or the end as telos or achievement, We must take seriously these two fantasies… they are what makes writing and reading happen.

I called this process ideality, as the implied end is an “ideal” form to which no more improvements can be made. I borrowed this idea from an essay by Jacques Derrida, where he talked about words being comprehensible - despite the different accents and contexts they can be spoken in - partly because they have an “ideal” form against which we measure each utterance. I say tomato, you say tomato, and we both think vegetable.

The meaning of tomato though… I had to leave Kansas to find that one out. I never fully understood Derrida’s argument, but it seemed to involve the meaning of words “leaking” from their ideal form into both their relations with other words, and the contexts in which they’re used. Confused? Don’t worry, it will only take 25 minutes to ketchup. Think that sort of thing (careful now).

Each chapter of my thesis was about a game which had links to another medium, and in each instance I used ideality as a frame to describe these links and leaks; a lens you could look through to see the ideal form beneath each incarnation of the same story. One chapter looks at the links between Metal Gear Solid and a Japanese writer called Kōbō Abe. Another at EVE Online and Ayn Rand. In total it took about 5 years to write. It ends with a poem.

With pens and typewriters, you think you know how it works, how “it responds.” Whereas with computers, even if people know how to use them up to a point, they rarely know, intuitively and without thinking – at any rate, I don’t know – how the internal demon of the apparatus operates. What rules it obeys. This secret with no mystery frequently marks our dependence in relation to many instruments of modern technology. We know how to use them and what they are for, without knowing what goes on with them, in them, on their side.

Ten years ago I’d read and re-read passages like the above, convinced that with enough effort I’d one day be able to understand them. I’d pick out individual sentences - “secret with no mystery”, how good is that - and type out giant swathes of text into a private blog of all my notes. I’d panic that I knew nothing, then write as if I knew everything.

One June Saturday I sat for hours in the library at Senate House, inching my way through Paper Machine one line at a time. That was the day I realised that what I was reading would never make sense - at least, not in the way I’d thought. It wasn’t like learning a language, where fluency would one day inhale the fog which surrounded every word as I plodded along, two pages an hour. It was all a bit more subtle than that.

Derrida talked about nothing but always seemed like he was saying something, even when you couldn’t say what. The fact that you couldn’t seemed to be what he was saying. The meaning of it all was there, but as a feeling, not a thought. A ghost in the machine. A daydream. A misunderstood quote on an unread blog.

I remember staring out the window and thinking about playing Metal Gear Solid as a teenager, and having the same reaction to the uncanniness of that game as I was to the essay in front of me. I closed the book, and met my best friend in The Knights Templar to tell him all about it.

I think he smiled. I do now looking back. Beers with the lads on a Saturday afternoon; the différance of a Hepcat. Who cares if you’re lost on the yellow brick road…